Ingmar Bergman: The Best of

Share

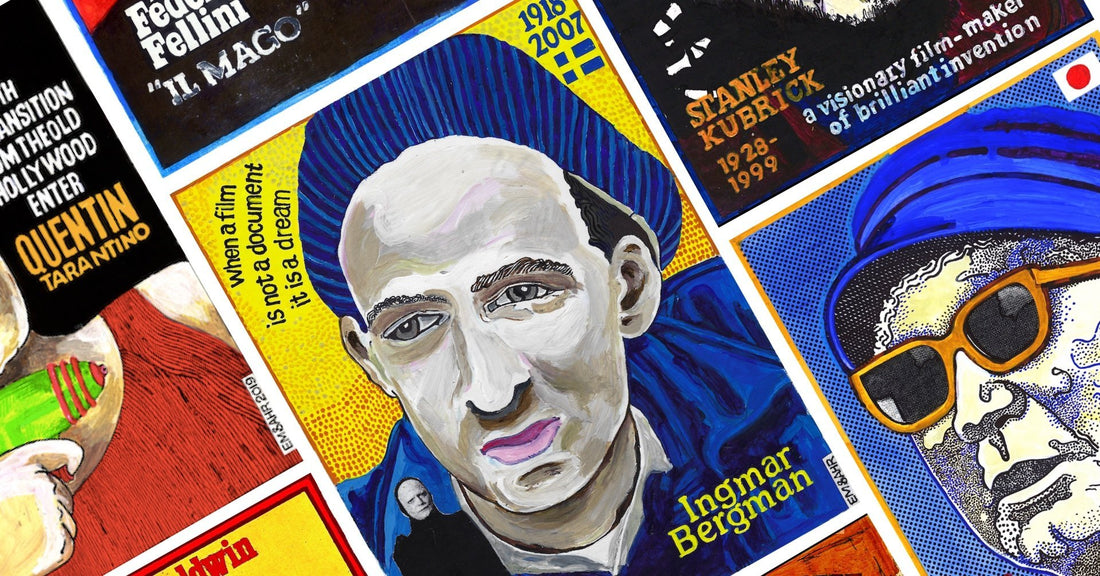

INGMAR BERGMAN

by Arianna Munoz

Bergman on the set of The Seventh Seal

(July 14, 1918— July 30, 2007)

“When a film is not a document it is a dream.”

Dreams. That is the first word that comes to mind when thinking about Ingmar Bergman, the visionary Swedish director of film and theater. It is his films, though, that continue to capture the imagination. From the nihilistic nightmares of The Seventh Seal to the colorful imaginings of The Magic Flute, Bergman imbues every film with a dreamlike quality, our hopes and fears projected on the screen to be examined, criticized, and celebrated.

Born on July 14, 1918, in Uppsala, Sweden, Bergman grew up with his parents, Erik and Karin, and his siblings, older brother Dag and younger sister Margareta. The children had a strict upbringing; Karin was often cold and dismissive, and Erik wouldn’t hesitate to beat, cane, or lock the children up. Erik’s position as a Lutheran clergyman also meant that Bergman was enveloped by religious imagery from a very young age. As Bergman recalls:

"While Father preached away in the pulpit…I devoted my interest to the church's mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, the colored sunlight quivering above the strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceiling and walls…. that world became as real to me as the everyday world with Father, Mother and brothers and sisters."

It was a world Bergman later recreated in films like The Seventh Seal (1957), inspired by the medieval paintings on worn church walls depicting the unknowable mysteries of death, faith, and God. The tale of a medieval knight running from Death, The Seventh Seal is a nihilistic yet powerful depiction of questioning one’s faith. “Why is [God], despite all, a mocking reality I can’t be rid of?” mourns the knight, reflecting Bergman’s own fear of death and his grappling with religion, concepts Bergman only came to terms with years later. In The Seventh Seal Bergman openly addresses the existential concerns that have always plagued humanity, creating a stark and thoroughly unsettling masterpiece that continues to influence artists today.

"You play chess, don't you?" from The Seventh Seal

However, before his many masterpieces Bergman first had to find the magic lantern. The “magic lantern” was his name for the cinematograph, an early form of projector that projected slides or small reels of film. At nine years old Bergman longed for a cinematograph, and during Christmastime he got his wish, receiving the projector from his brother in exchange for a hundred tin soldiers. Placing the slides and film in front of the lamp, turning the crank to make the images move, Bergman became enthralled, a moment that would spark his love for directing, for creating stories all his own.

As a young adult Bergman attended Stockholm University, where he directed, acted, and wrote in student productions. He then entered the worlds of theatre and film, becoming the head of the municipal theatre in Halsingborg in 1944 and writing his first major script, Hets, or Torment, that same year. Because of the success of Hets, Bergman was given the opportunity to direct his own work, setting off a career that would span decades.

For Bergman, theatre and film were not mutually exclusive; his 1958 film The Magician revolves around theatricality, telling the story of a mysterious magician and his troupe seeking to con the wealthy leaders of a town. Both eerie horror and bawdy comedy, The Magician explores the conflict between private and public identity as the titular magician, Vogler, hides behind false beards, wigs, and makeup, struggling to hide his disdain for the people he entertains. Just as Vogler disguises himself, so did Bergman hide his private self, grappling with his controlled public persona versus his private “impulsive and extremely emotional” nature. Both these aspects of Bergman are evident in The Magician, the cool and collected exterior falling away to reveal the complex soul underneath.

"I hate them." Max von Sydow in The Magician

Bergman’s career took off in 1955 with Smiles of a Summer Night, a comedy on the flirtations between four men and four women. The film was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and set off a period during which Bergman produced some of his most influential works. The Seventh Seal was released in 1957, followed by Wild Strawberries (1957), The Magician (1958), and The Virgin Spring (1960), which won the Academy Award for best foreign film. Once only known in his native Sweden, Bergman had skyrocketed to international acclaim.

Bergman produced masterpieces well into the sixties and seventies. In 1962 he won his second Academy Award for Through a Glass Darkly, the first in a trilogy on the theme of faith followed by Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1963). Other films of this era are Persona (1966), Hour of the Wolf (1968), and The Magic Flute (1975). Directing all these films from Sweden, many on the island of Fårö, it seemed as if Bergman would never stop.

However, in 1976 Bergman was charged with tax evasion by the Swedish government, a scandal that profoundly humiliated him. Although later cleared of the charges, Bergman was so distraught that he went into self-imposed exile in Germany, remaining there until the 1980s. While there he made a few films including The Serpent’s Egg (1977), but upon looking back Bergman considered his time in exile to be a lost period of his career.

In 1982 Bergman announced his last theatrical film, Fanny and Alexander, a period drama inspired by Bergman’s childhood. After the “darkest despair” of his scandal, making Fanny and Alexander reignited Bergman’s love for filmmaking. The origins of Bergman’s passion for film, the magic lantern itself, returns in Fanny and Alexander as Alexander receives a cinematograph for Christmas and, like Bergman, is enraptured by its simple beauty. In rediscovering his love of filmmaking, Bergman returned to the fateful Christmas night when the spark of inspiration was first set off, his childhood dreams inspiring his adult reality.

After Fanny and Alexander Bergman continued to write and direct television specials, some later released theatrically. In 2003 Bergman released his final film, Sarabande, to great praise, and subsequently retired from filmmaking. Four years later at the age of 89, Bergman died peacefully in his home on Fårö, the island that had been the centre of his greatest productions.

Although the dreamer himself has passed, Bergman’s films still have an extensive influence on modern culture, impacting everything and everyone from Woody Allen to Richard Ayoade to the Bill and Ted film series and Monty Python’s Meaning of Life. Bergman’s films retain a timeless quality, tackling themes like faith, identity, and hope with such care and precision that the viewer is instantly invested. Conjuring worlds where men can play chess with Death, where the Queen of the Night sings to an awestruck prince, where a little boy can find a magic lantern in a simple projector, Bergman continues to prove himself a master magician, a creator of dreams both beautiful and terrifying, films that remain in the audience’s mind long after the screen has gone black.

by Arianna Munoz

Quotes, all from Bergman’s autobiography The Magic Lantern:

“Sometimes there is a special happiness in being a film director. An unrehearsed expression is born just like that, and the camera registers that expression.”

“Film as dream, film as music. No form of art goes beyond ordinary consciousness as film does, straight to our emotions, deep into the twilight room of the soul.”

“Sometimes I dream a brilliant production with great crowds of people, music and colorful sets. I whisper to myself with extreme satisfaction: This is my production. I have created this.’”

Videos:

“Bergman’s Dreams – An Original Video Essay” from the Criterion Collection, written and directed by Michael Koresky

1 comment

Loved It!