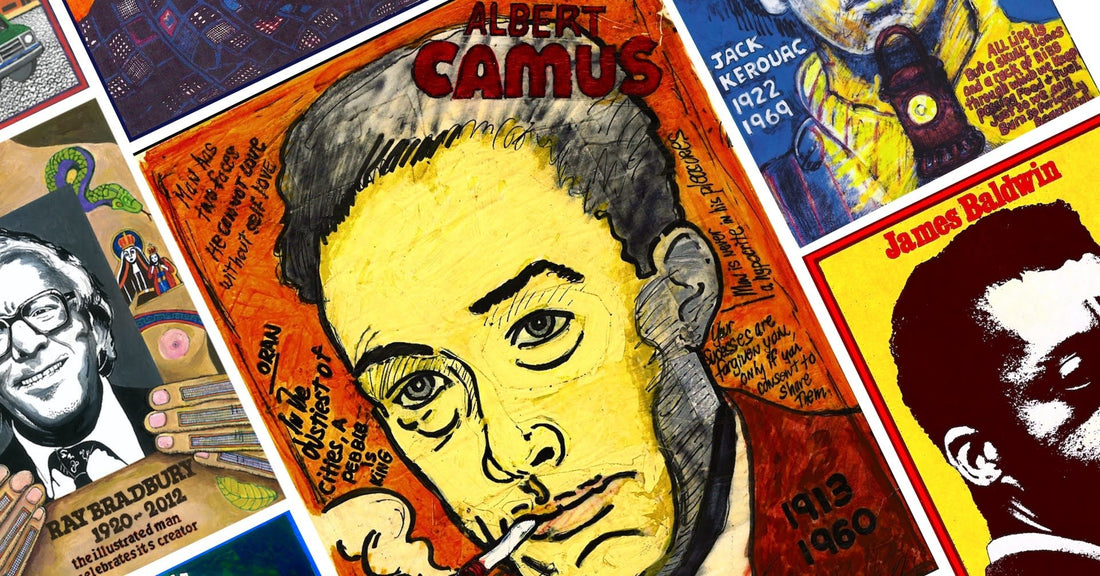

Albert Camus: The Rebel Philosopher of the Absurd

Share

Albert Camus: The Rebel Philosopher of the Absurd

Albert Camus was born on November 7, 1913, in Mondovi, a small town in French Algeria. His father died in World War I when Camus was just a year old, leaving him to be raised by his mother, who worked as a cleaning woman. Growing up in poverty, Camus developed both a deep sensitivity to suffering and a fierce determination to find meaning in a world that often seemed indifferent.

As a young man, Camus studied philosophy at the University of Algiers, where he began shaping the ideas that would later define his career. Though often associated with existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre, Camus rejected the label. He insisted he wasn’t an existentialist but something else entirely—a thinker of the “absurd.” For Camus, the absurd was the confrontation between humanity’s constant search for meaning and the universe’s silence in response.

This outlook made Camus a contrarian voice in philosophy. Where some thinkers sought religious faith, political ideology, or metaphysical answers, Camus argued that the world offered none. Instead, he urged people to embrace life fully, even in its absurdity. His novel The Stranger (1942) embodied this worldview: its protagonist, Meursault, confronts life and death without illusions, living authentically in the face of meaninglessness.

Camus’s essays deepened these ideas. In The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), he reimagined the Greek tale of the man condemned to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity. For Camus, Sisyphus symbolized humanity: forever struggling without ultimate purpose. Yet, Camus concluded, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” His contrarian stance was clear—rather than despair, he urged rebellion against meaninglessness by embracing life as it is.

Camus was also a man of political conviction, another arena where he challenged popular thinking. During World War II, he joined the French Resistance, editing the underground newspaper Combat. He stood firmly against fascism, but he also rejected communism, breaking from Sartre and other intellectuals who defended it. For Camus, totalitarianism of any kind—whether from the left or right—was an assault on human dignity. His book The Rebel (1951) further examined this, arguing that rebellion must seek justice without turning into tyranny. This refusal to conform to the dominant ideologies of his era made him both admired and controversial.

In 1957, at the age of 44, Camus received the Nobel Prize in Literature. The award recognized not only his novels and essays but his ability to illuminate the human struggle with honesty and moral clarity. True to form, he accepted the prize humbly, dedicating it to his teacher who first encouraged him to pursue writing.

Tragically, Camus’s life was cut short. On January 4, 1960, he died in a car accident in France at just 46 years old. In his car was the unfinished manuscript of what would have been his next novel, The First Man.

Albert Camus’s contrarian viewpoints continue to resonate. He rejected comforting illusions, refused to align with political dogma, and insisted that human beings could live with dignity in an indifferent universe. For Camus, life’s value came not from eternal truths but from how we live each day—with honesty, courage, and defiance.

He remains the philosopher who reminded us that even in a world without ultimate meaning, there is beauty, freedom, and a profound responsibility to live well.