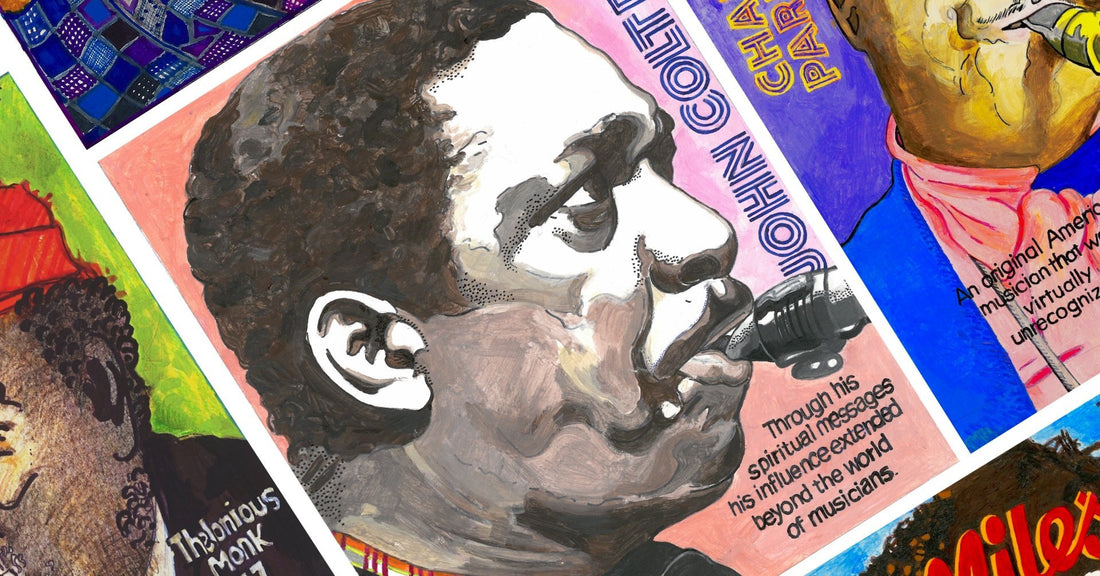

John Coltrane: The Best of

Share

John William Coltrane

September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967

By Spencer Rubin

Coltrane’s legacy is that of a shooting star who shone brighter than any in the sky, but for a fraction of the time. Before he was 40, he was featured on and composed over 100 albums, which effortlessly blended genres, cultural influences, and styles [1]. His most acclaimed and revered albums, Blue Train, Giant Steps, My Favorite Things, and A Love Supreme, were released in the span of ten years and garnered him a long list of certifications across the world, while he rapidly developed as a musician and composer [2][3][4]. His meteoric rise to jazz acclaim and his innovative playing made him a trailblazer in the 1960s, and his ability to vocalize his message through his horn made him a holy figure among superfans. Coltrane often talked of leaving his physical body while on stage, projecting his astral being, his spirit, and soul, out to the crowd.

Music surrounded John William Coltrane as a child. He was born in September 1926 and raised in Hamlet and High Point, North Carolina, where his grandfather, Reverend William Wilson Blair, was a well-known gospel minister, and his father, John Robert Coltrane, was a preacher [5][6]. When John R. Coltrane wasn’t at church, he would sit in the living room, deftly switching between instruments to entertain his young son. John W. looked up to these men and the blues players he heard on the radio, like Count Basie and Lester Young [7]. Coltrane’s music was heavily influenced by the soulful sounds and sorrowful lyrics of the blues, hints of which brood in his dark, gospel-like tones.

“My music is the spiritual expression of what I am — my faith, my knowledge, my being.” – John Coltrane

Coltrane’s life was abruptly uprooted when he was 12. His father and grandfather passed away suddenly, and within months so did his grandmother and an aunt. This triggered a period of severe financial distress for his mother, Alice. The two moved in with relatives in New Jersey, and the young musician focused his grief on mastering the clarinet.

When he graduated high school and moved to Philadelphia in 1943, he had one thing on his mind: a career in music. Bebop musicians like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were peaking on the charts, and Coltrane wanted to learn how to play with them. He studied Johnny Hodges supporting Duke Ellington and Dexter Gordon leading the bebop movement. But after a few semesters at the Ornstein School of Music studying saxophone, Coltrane was enlisted in the Navy and shipped off to Hawaii.

When he graduated high school and moved to Philadelphia in 1943, he had one thing on his mind: a career in music. Bebop musicians like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were peaking on the charts, and Coltrane wanted to learn how to play with them. He studied Johnny Hodges supporting Duke Ellington and Dexter Gordon leading the bebop movement. But after a few semesters at the Ornstein School of Music studying saxophone, Coltrane was enlisted in the Navy and shipped off to Hawaii.

At Pearl Harbor at the close of the war, fellow musicians quickly noticed Coltrane’s dedication to his craft and recognized his superior playing. He was asked to be the first black member of the Navy band, challenging modern music before recording his first piece – done with a quartet of fellow sailors on Oahu in 1946 [8][9]. Coltrane returned to Philadelphia with life and industry experience and invoked the G.I. Bill to enlist at and graduate from the Granoff School of Music.

Coltrane hopped from group to group, blowing for anyone who’d hire him. He worked with Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, Jimmy Heath, and Dizzy Gillespie, moving between genres and bands effortlessly and earning a reputation as an especially talented musician with a deep understanding of music. He was a hot commodity in Philly from 1946 to 1955 as he learned to improvise with the greats, switching from blues to big band, alto to tenor sax.

During the early ’50s, when Coltrane was playing with Jimmy Smith and Miles Davis, he fell into heroin addiction, a crutch that caused many band leaders – over 6 years – like Duke Ellington and Davis to fire the young star. Though his dependency proved him an unreliable employee, when he was in the studio, he made magic.

And Davis was enamored with Coltrane’s “voice on tenor,” allowing him to explore his sound and style. Coltrane referred to his peer as “Teacher,” and, together, they obsessively discussed and practiced theoretical music concepts. They produced a multitude of acclaimed albums, including The New Miles Davis Quintet (1956), ‘Round about Midnight (1957), and Kind of Blue (1959).

In 1957, Davis walked in on Coltrane in the midst of an overdose. Fellow bandmate and drug buddy, drummer, Philly Jones, helped Coltrane through the night, and Davis was compelled to fire them both. Coltrane was devastated. He needed to make changes, or he would never be able to share his message. He booked a trip home to Jersey, where he locked himself in a bedroom to dry out, cold turkey. It was an incredibly tough time for the musician, and he’d later credit these days with inspiration for his most acclaimed pieces. He left his family’s home refreshed and eager to get back into Philly’s jazz scene and into the studio.

During Coltrane’s hiatus from Davis’ band, he practiced almost constantly. He began to develop what would be the base of his signature style, wrapping pentatonic scales around each other, deconstructing scalar patterns, and layering harmonics to create his distinctive “sheets of sound.”

That same year, Coltrane met legendary pianist Thelonious Monk. Coltrane and Monk spent the summer of 1957 recording Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane (1961), with Monk guiding Coltrane directly through unique melodic and rhythmic shifts and pauses.

In 1957 Coltrane was signed to Prestige, and he began to lead his own band (Coltrane) and compose his own music (Blue Train). At the same time, Miles Davis was experimenting with a new style of “modal jazz,” within which Coltrane’s new format fit perfectly. They began to play together again after a nine-month break, experimenting and growing, and finally recording Davis’ most successful album, Kind of Blue.

Coltrane continued to release albums: Blue Train (1957), Soultrane (1958), and the revolutionary Giant Steps (1960). By the end of his four years with Davis, Coltrane had turned from a Philly bar and club stage staple to an internationally renowned musician, his fame cemented by Giant Steps.

Giant Steps was the first of Coltrane’s albums that shaped the “post-bop” movement. It was Coltrane’s debut on Atlantic Records, leaving Davis’ group and Prestige behind to form his own quartet. He composed the album’s entirety. Giant Steps reflects a shift from structured bebop to a new, avant-garde, “free jazz,” inspired by Ornette Coleman, who Coltrane enlisted for lessons. The songs on Giant Steps, like “Naima,” “Cousin Mary,” and “Giant Steps,” shirk traditional chord changes for melody-driven, passion-fueled bursts of looping, winding saxophone, backed by driving bass and tapping drums.

Coltrane recalibrated for My Favorite Things (1961), bringing in new musicians and ideas for his final work with Atlantic. The album’s title track is a reimagined version of the song of the same name from the movie The Sound of Music (1965). McCoy Tyner on piano works in harmony with Coltrane, embarking on an in-depth exploration of the familiar waltz. The band rotates through different variations of the song, enticing listeners with each bar, each note challenging the familiar tune. Coltrane learned soprano sax for the album, and the single, “Favorite Things,” propelled to the top of the charts, making this his most commercially successful album, and John Coltrane a household name.

Enlisting the musicians from Favorite Things and signing with Impulse Records, Coltrane composed several more albums. His signature brooding notes and sheets of sound, his masterful improvisation, and his abilities as a conductor pushed the quartet’s playing to unmatched levels. They riffed on endless variations of the same chord, keeping tune with the bassist and drummer, as Coltrane wove his horn blasts between his bandmates’ notes.

Jeff Brownell wearing a John Coltrane design by Em & Ahr on the set of Armstrong Now, 2020

Coltrane and his bands at Impulse produced a variety of sounds from 1961 through his death in 1967. With his quartet, he released traditional jazz records like Ballads (1963), and with a quintet featuring his wife Alice, he toured the world and recorded live. He put together a full brass band for Africa/Brass (1961) and Ascension (1966).

“The main thing a musician would like to do is give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things that he knows of and senses in the universe.” –John Coltrane

Up until 1964, however, Coltrane was preparing for his magnum opus: A Love Supreme.

A Love Supreme challenged all perceptions of contemporary music when it was released in 1964. It was a dedication and a thank-you note to Coltrane’s God, the one that got him through the dark days of addiction, and the one who Coltrane leaned on during his days holed up in Jersey, sick with withdrawal. A Love Supreme is Coltrane’s previously-realized potential fulfilled. It is filled with unconventional runs and changes, pure bursts of energy and emotion that devolve into screeches and scratches. Each note, however, is intentional, each awkward blast of every phrase penned deliberately.

The finale of the four-track album is the smooth, then suddenly chaotic, “Psalm.” Young listeners, looking for alternative spiritual paths from their conservative, puritan parents, were intrigued by the unconventional sounds. They soon noticed that the inscription on the inside album cover matched “Psalm’s” horn blasts note for note. Coltrane’s divine cries of pain and passion, shared through his instrument, could be read while listened to. This was a powerful revelation for many, who had never considered literal meaning in instrumental music. A Love Supreme became Coltrane’s highest regarded composition, putting him up for Grammy nominations and Hall of Fame inductions [10][11]. It was performed live only once, to a shocked crowd in Antibes, France [12].

Coltrane had grown up the son and grandson of preachers and with a spiritual mother. Family members, reflecting on his legacy are not surprised that John Coltrane blossomed into a religious faithful, and spiritual leader. He was steeped in holy tradition, and as he grew older and faced dramatic challenges only faced by heroes and geniuses, his faith was the only thing that pushed him through the struggle to greatness. He leaned on faith and music through his tragic youth, addiction, the barriers placed in front of black Americans, to a career that would expand and alter contemporary music. Coltrane’s biographer, Lewis Porter laughs as he ponders the St. John Coltrane Church in San Diego: Not many artists have churches dedicated to studying and living by their words and compositions [13][14].

Coltrane was not the first musician to be considered a godly figure, and he was not the last. Soon after Coltrane’s success, Eric Clapton was compared to God during his time with John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, and Jerry Garcia was seen as a prophet as the frontman of the Grateful Dead [15]. Throngs of Deadheads have dedicated their lives to following the band (and subsequent spin-offs like The Dead and Dead and Co.) to forever be in the presence of the music, like Jews traveling to pray at the remnants of the first temple in Jerusalem or Muslims to the Kaaba in Mecca. For some, spirituality is awakened while tuning in to Jerry’s guitar and Coltrane’s horn [16].

The space that instrumental music like a bluesy Clapton solo, a 20-minute Dead jam, or A Love Supreme leaves for listener interpretation is boundless, leading trains of thought through our minds. The lyrical insertion of A Love Supreme, paired with Coltrane’s soulful sound, introduced many uninitiated music fans to unique, conscious, and subconscious paths, introspective and spiritual experiences.

Reflecting on Coltrane, however, members of the Dead cite Africa/Brass as their biggest conscious inspiration. The African rhythms and beats – which Coltrane’s drummers built off of for the next 6 years – profoundly impacted musical conceptions for Phil Lesh and Bill Kreutzmann, bassist and drummer of the Dead. Lesh can be heard playing the bassline from “Greensleves” from Africa/Brass in various renditions of the Dead classic, “Clementine.” The Dead also drew heavily from principles that Coltrane introduced on Favorite Things, specifically the concept of using one chord to create endless riffs and runs, constantly evolving jams. Bob Weir, guitarist, and singer for the Grateful Dead states that he was inspired by McCoy Tyner’s exploration of chords. The jam band was looking for ways to extend their jam sessions and turned to the modal techniques that Coltrane and Tyner used to continuously change their playing while maintaining the structure of the song [17].

Any musician or band that impacted the Grateful Dead, especially their legendary improvisational jam sessions, has infinite influence, as the Dead is considered by many to be the perennial “jam band,” having sparked a fuse for generations of new sounds and structures. They paved the way for bands like the Allman Brothers, Phish, and Widespread Panic, who specialize in captivating and engaging audiences with blues roots and rambling instrumental sections.

After the release of A Love Supreme, with his true message out, Coltrane began to delve deeper into musical exploration. He focused on polyrhythms and discordant tones and notes, breaking up his quartet, frustrated at Coltrane’s obsession with pure expression. His wife Alice took over for Tyner on piano, and they produced increasingly spiritual and experimental albums like Ascension, Kulu Se Mama (1967), and Om (1968). John and Alice recorded and released music up until a few weeks before his death from liver cancer in July of 1967 [18].

After the release of A Love Supreme, with his true message out, Coltrane began to delve deeper into musical exploration. He focused on polyrhythms and discordant tones and notes, breaking up his quartet, frustrated at Coltrane’s obsession with pure expression. His wife Alice took over for Tyner on piano, and they produced increasingly spiritual and experimental albums like Ascension, Kulu Se Mama (1967), and Om (1968). John and Alice recorded and released music up until a few weeks before his death from liver cancer in July of 1967 [18].

Coltrane had stood in such prominence at the forefront of pop music and culture that without his presence pushing music, there was a hole in the industry. He was posthumously recognized by the Library of Congress and inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame after being awarded their Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997 [19]. He was honored with a Pulitzer Prize for a lifetime of innovative and influential work [20].

John William Coltrane lives on through music school requirements and mentions in Hollywood; his name adorns street signs across the United States. His songs are on lists of the most influential of all time, and when Barack Obama was elected, he hung Coltrane’s portrait in the halls of the White House, an honor to the sax-man who changed contemporary music with truth, faith, and infinite innovation.

2 comentarios

A brilliant article……well-researched, comprehensive and superbly written!!!

Love your EVERYTHING 🔥